There are some seriously spooky coincidences in Beatles history. Here are two:

The classic Beatles song “She’s Leaving Home” — a composition which the late Pulitzer Prize-winning American composer Ned Rorem called “equal to any song that Schubert ever wrote” — was written by Paul McCartney after he came across an article in The Daily Mail about a 17-year-old runaway.

Incredibly, and completely unbeknownst to him, McCartney had met the very girl in the article years before. Even more incredibly, there is film of that encounter: in 1963, 13-year-old Melanie Coe was a contestant in a miming contest on the British TV program “Ready, Steady, Go.” The judge who picked her as the winner and presented her with an autographed album, was 21-year-old Paul McCartney. To watch this clip with She’s Leaving Home in mind — Melanie Coe is the young girl dancing and miming on the far right and McCartney may as well be a lifetime away from who he would be in 1967 — is truly an exercise in the surreal.

The backstory of “Eleanor Rigby” is at least as strange. McCartney has said that Eleanor Rigby began as “Miss Daisy Hawkins.” (Folk singer Donovan says Paul visited him once and played him the song-in-progress when the name was “Ola Na Tungee.”) Paul changed the name to Eleanor because he liked the name of the actress, Eleanor Bron, who had just starred with the Beatles in their second movie Help! Wanting a more natural-sounding surname, he settled on Rigby after coming across a wine and spirits shop called “Rigby & Evans” in Bristol. In a crazy historical twist, it was discovered — years later, in the 1980s — that a Liverpool cemetery contained a grave whose headstone actually bears the name Eleanor Rigby.* Even crazier, Paul and John used to take shortcuts through this very cemetery as youths (it is situated in Woolton, near where John grew up, and was where John’s uncle George Smith was buried). Perhaps craziest of all, given the song’s lyric, the real Eleanor Rigby toiled as a scullery maid; and is not even the principal honoree of the headstone, appearing a full 4 names below a “John Rigby.” (Buried along with her name, indeed.)

*To this day, McCartney insists he never knew this obscure Liverpool headstone existed, though he acknowledges the possibility that he could have come across it as a youth and had the name lodged in his subconscious. In 2017, when the deed to the grave was put up for auction with hopes that its putative Beatles connection would fetch a premium, McCartney issued the following statement: “Eleanor Rigby is a totally fictitious character that I made up. If someone wants to spend money buying a document to prove a fictitious character exists, that’s fine with me.”

There are others too numerous to review here. (Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In — the first volume of his mammoth in-progress Beatles biography — reveals, for example, that a dizzying array of previously unknown happy accidents, happenstances and luck conspired to save the Beatles from oblivion after the young group were rejected by virtually every record label in England.)

But one of the most interesting and historically important convergences has to do with a date on the calendar that passed last week: November 22.

The assassination of President Kennedy has long been a part of Beatles historiography. The murder of the youthful and charismatic president on November 22, 1963 — carried out in broad daylight and captured on amateur film — traumatized the country. Two and a half months later, with the national wound still fresh, the exotic, exuberant young Beatles landed in America amidst a frenzy of anticipation, record sales, and saturation radio coverage. Beatlemania overtook the country practically overnight.

There’s a chicken-and-egg element to this JFK-Beatles convergence: did The Fab Four rescue a sleepwalking America from a cloud of gloom, or was America hankering for something, anything, to get excited about?

Or was there no convergence at all — just a myth fashioned by coincidence and hindsight?

That a pall hung over the country after JFK’s assassination is clear from a glance at any benchmark of popular culture. In the week after Kennedy’s death so few people attended the movies that Variety didn’t even publish box office figures. When they returned, mindless froth – Under The Yum-Yum Tree, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, and Charade – monopolized the box office.

Similarly — in what was perhaps the musical low point of the rock era — the biggest records in December 1963 and January 1964 were The Singing Nun’s “Dominique” and Bobby Vinton’s “There! I’ve Said It Again.” There wasn’t much relief further down the charts either. Save for a precious few exceptions, the two months between the Kennedy assassination and the arrival of the Beatles was a musical abyss of instrumentals, novelty records, and Hollywood teen idols.1

Coincidental or not, this cultural malaise was a fitting metaphor for the depression that gripped much of the country.

Listen to Emmylou Harris’s vivid recollection . . .

“When the Beatles came along, all of a sudden it was alright to feel joy”

There is, to be sure, a debate over how much one thing had to do with the other and whether connecting the Beatles’ impact to JFK’s assassination is a revisionist exercise. Jay Jay French has long been fascinated with the story of Kennedy’s assassination and its aftermath. He suggests that while the event had a profound effect on the course of American history, the Beatles connection is an open question:

Had Kennedy not been assassinated Lyndon Johnson would not have been able to pass The Civil Rights Act. It’s a very important thing to keep that in mind. That never would have happened. And then of course the question of would the Beatles have been as big as they were, because they happened two months after Kennedy was assassinated. And that’s always been a question that sociologists ask themselves. I’m a huge Beatles fan and I’m not sure I know the answer to that, because the Kennedy assassination was so traumatic.

Iconic producer Joe Boyd is among those who dismiss the theory that the Beatles’ popularity in America was a product of the gloom following the Kennedy assassination:

I think it just comes down to the fact that it was so good. You know, there were plenty of beat groups around in Britain, having the same influences, and they didn’t make music like that. I think in music I subscribe to the “Great Man” theory of history, you know, that it’s not historical forces, it’s individuals who turn the course of history. And I think that the Beatles were just brilliant individual musicians who imposed themselves on the world.

At the 2014 TCM Classic Film Festival, Alec Baldwin and Don Was, discussing the impact of the Beatles in the context of the 50th anniversary of the movie “A Hard Day’s Night,” also downplayed the role of JFK’s death.

Baldwin: When we talked backstage you said that it even goes back to the Fifties — it wasn’t just, as some people think, oh, Kennedy’s assassination and people needed this release or what have you — you said things that were going on in this country even in the Fifties fed into the Beatles’ ascent.

Was: Oh, I think it was set up for decades really. You had this postwar prosperity where young people were suddenly going to college and having time on their hands to think about philosophical issues; you had the predominance of TV, global TV for the first time, connecting the world. And we’re aware of what’s going on in the world, we see the results of war, and suddenly there’s a kind of distrust of authority. [There’s] an educated youth group, the baby boomers are the largest demographic group of the time. And it was primed for a youth revolt against the conservative kind of complacency of the Fifties.

Slate magazine went even further and published an entire article debunking the JFK-Beatles connection. Some of the assertions in the piece are dubious, but hey, like Jay Jay French said, sociologists are divided over the issue.

The problem is that if the JFK-Beatles theory is a truly revisionist construct we have to disregard the very personal recollections of many people who were around in 1963/1964 — or worse, ascribe revisionism to their own memories. And like Emmylou Harris’s, those memories are pretty compelling.

Tommy James: All of a sudden came the Kennedy assassination. A lot of people said, and I believe it’s true, that the only thing that made 1964 bearable after what the assassination did to the country was the Beatles. I happen to believe that’s accurate. Because everybody was so saddened and heartbroken when John Kennedy was killed. For me, the Beatles and that event, the assassination of President Kennedy, always stays in my mind as almost one and the same.

Actor Ed Begley, Jr: You know, the horrible assassination of JFK — part of the reason I and many of my friends were able to recover from that was the gift that the Beatles gave us: we started to feel good again, after that horrible thing with the loss of our president. It was one of the joys that began to creep in our life, their music. So they’ve been a very good friend to America in many ways.

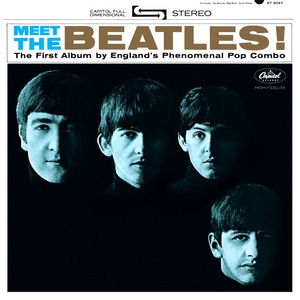

Billy Joel: I remember the country had the blues. My age group was kind of detached from the establishment stuff. After Kennedy was shot, nobody believed that a flunky like Lee Oswald did it; everybody thought it was a conspiracy. Everybody was just so taken aback by the assassination of this young, vital president who represented us. We thought he was like us. He was our guy, representing youth and progress. So when the Beatles came, they filled that vacuum in a way: all of a sudden, they now represented us, instead of that president who was dead. It all kind of coalesced with the release of Meet The Beatles!, and [then] The Ed Sullivan Show. We went crazy, my age group went insane. They filled up the vacuum that was left when Kennedy was taken away. And we were all kind of as one – we were a community now, again, because of the Beatles.

Chris Hillman: The Beatles just totally came out of left field. I really credit them — now, you may think I'm crazy — but the Beatles were a real healing force. They came out just after John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963. All of a sudden comes this fresh, energetic, just unbelievably exciting band . . . they opened the floodgates for everybody.

George Thorogood: I saw the Beatles on TV, and they were the first people I ever saw — ever — that looked happy. Now this is a few months after Kennedy was assassinated. In those days, I never saw any happy people. Guys hated their job. Parents never got along, the brother’s always getting beat up, there were fights all the time. Unless it was somebody in a movie, who was faking it — you know, an actor — I never saw anybody that was really happy. I never saw anybody smiling, in my neighborhood. And I looked at the Beatles and said, those guys are the first people I’ve ever seen happy! But they did that for everybody, I’m not the only one. And anybody who says different, who was born after 1950, is lying to you.

Richie Sambora: They were the most incredible thing I ever saw. I couldn't put it into any kind of historical context at the time — I couldn't connect it with the Kennedy assassination — but I knew that I was witnessing something truly life-changing. And not just for me, but for everybody as well. Beyond that, they did something even more important: they made people feel good. They gave people hope. They brought people together. Don't they give out Nobel Prizes for that sort of thing, and how come The Beatles haven't gotten any?

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Dom Famularo, a renowned drum teacher and clinician who has been called Drumming’s Global Ambassador, hosted a podcast with other musicians and wondered aloud what kind of healing music might come out of the global shutdown.

If you think about the timing of the Beatles — a very important part of it was we had just seen, and witnessed, a U.S. president get assassinated the November before. So the world was in mourning. This band came by and had 73 million people [watching] a television show in America, and gave us hope . . . happiness . . . love . . . unity. They delivered to us a message. So I ask you now, in the time of this incredible pandemic: This is a very serious time. . . what kind of music should be delivered, now, that can give the world hope and humanity?

Now, obviously, the assassination of John F. Kennedy didn’t cause American youth to embrace the Beatles. Nor did the Beatles single-handedly turn the United States from a mausoleum one day into a dance party the next (although some people — Little Steven van Zandt, Tom Wolfe and Allen Ginsberg among them — imply something very close). But one thing these recollections and the examination of contemporary music and film suggest is that the assassination’s lingering fallout served as something of a lid on excitement. Think of the the way a teenager at a somber event feels pressure to suppress laughter or horseplay. On a macro level, that’s what the national mood was for weeks after Kennedy’s assassination: one long somber event, as if the whole country would have shouted “too soon!” at anyone caught enjoying themselves too much.

That pressure, for whatever reason, seems to have been relieved by the arrival of the Beatles. In fact, whether or not the whole assassination-Beatlemania theory is historical revisionism is almost beside the point. It’s enough that America was depressed for weeks after Kennedy’s death, and that the Beatles were the first entertainment phenomenon after the assassination and that American youth did unite around them in almost orgiastic excitement. The collected testimonies here by people who were all young when JFK was shot effectively confirm that their entire generation responded to the Beatles like a shaken bottle of champagne finally uncorked.

Tommy James, above, said something interesting: that for him the Beatles arrival and Kennedy’s assassination are “one and the same.” In another interview he alludes to the dark/light, yin/yang duality of this confluence. “The Beatles’ career beginning and the Kennedy assassination are in my mind at the same time. And it’s really a shame isn’t it, in so many ways, to have those two events linked. But that’s what’s in my mind.” In putting it this way, James unwittingly touches on something more than the simple chronology of JFK’s death and the Beatles’ arrival: that is, the assassination of John F. Kennedy signalled the end of an era, while the arrival of the Beatles heralded the beginning of another. Journalists who lived through these two events are particularly quick to recognize this.

Bob Herbert: Nineteen sixty-four was the year the 60s really began. For a decade known for its excitement, the 60's got off to a decidedly slow start. Doo-wop music was still around, and dreamy songs of widely varying quality — "Moon River," "Where the Boys Are" — were among the biggest hits. It was a quiet time. The average annual salary was $4,700, and a favorite pastime was bowling. There was no reason to think that radical changes were brewing when 1964 debuted. The nation was still in shock and mourning over the murder of Jack Kennedy the previous November.

And then in February, suddenly and without warning, the Beatles were upon us. If you spend just a little time reflecting on the Beatles you come away astonished by the changes they wrought (or came to symbolize) in what seemed like a split second of real time. People dressed differently, wore their hair differently, danced differently . . . The Beatles blew in like a sudden storm and permanently altered the cultural landscape.

Steven D. Stark: When historians go back and look at the second half of the 20th century, they will recognize that the Beatles were historical forces in a way that artists and musicians had never been before and probably will never be again. There was something about them and the times in which they made their music that made the whole thing unique. That is important.

Mark Bowden: For those of us whose first impressions of the larger world — brought to us in dramatic images on television and in LIFE magazine — were the Cuban Missile Crisis, when civilization itself teetered on the brink of destruction, and then the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and his killer, Lee Harvey Oswald, the Beatles arrived as an affirmation of joy, youth, pleasure, creativity — and the future.

If there’s one aspect of the JFK-Beatlemania linkage that can only be made in hindsight, it’s this handing of the baton from one epoch to another. In 1964, the assumption could only have been that the Beatles were a temporary teenage distraction; no one could foresee the changes in the band, popular music, the country and the world over the rest of the decade, much less that those changes would render the pre-1964 world ancient by comparison, or that they would still reverberate nearly sixty years later, or that the Beatles would be permanently fixed among the symbols of an altered Western society.

All of which only makes the Kennedy-Beatles synchronicity, whether random or causal, even more remarkable. Because now we come to the piece de resistance of this accident of historical timing — an irony that we can now look back at, wide-eyed, as one of those eerie examples of “fate” — and which lies hidden in plain sight. . .

So far we’ve examined the Beatles’ American impact in general terms, using February, 1964 as shorthand for their arrival and effect on American youth. In actual fact, Beatlemania in the U.S. began to spread in late January. This is an important distinction, because Americans had not yet experienced the Beatles. With their momentous performances on The Ed Sullivan Show still a few weeks away, the craze was driven by their records, mainly their first Capitol releases: the single, “I Want To Hold Your Hand,” and the album it led off, Meet The Beatles! 2 Each was a phenomenon. They exploded almost simultaneously and stayed atop the single and album charts for months. When people talk about the Beatles lifting the national mood after weeks of post-assassination trauma, it’s these records that lay the groundwork, feeding the mania that kept growing right up to the Beatles’ arrival at Kennedy (!) Airport on February 7, and through their debut on the Ed Sullivan Show two nights later.

The cherished place which Meet The Beatles! holds in the hearts and minds of American musicians will be the focus of a future Let Us Now Praise installment, but what’s relevant here is its role in the Beatles-in-the-wake-of-JFK story. That role needs to be stressed.

Pat DiNizio: I came across a magazine, American Heritage I think, that said 1964 was the year that changed everything. It dealt largely with the Vietnam War, student protests, the assassination of JFK — but also with Beatlemania and the profound impact it had on the youth of America. I think the Beatles lifted the spirits of the entire world. . . and Meet The Beatles! is arguably the most historic rock ‘n roll album ever made.

Steve Lukather: Meet The Beatles! was the “on” switch to my life, and every song was magic. The sound was otherworldly to me, as if something from another place and time came to touch me. And that feeling is still there for me and for everyone I know that was there in real time. Not “retro” but real time. You had to be there and live through it all, really, the way the Beatles changed everything. Kids today could never understand it. It was not like some teeny bop shit. It was real, and still is.

Ian McNabb: Americans were still in a bit of a Bobby Darin period — they were on a downer ‘cos of the Kennedy thing and the Cold War — and Meet The Beatles!, this explosion of energy from some place they’d never heard of, just really knocked them on their ass.

As Billy Joel said, American Beatlemania “all kind of coalesced with the release of Meet The Beatles!”

So, now: consider the historical linkage between the Kennedy assassination on November 22, 1963 along with its extended national trauma, and the arrival to national delirium two months later of the Beatles and the advent of a new era in popular culture.

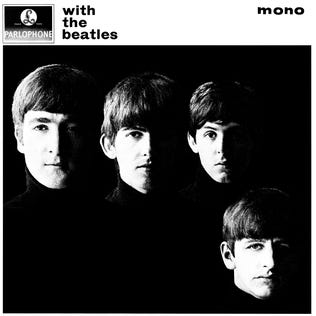

Now consider that Meet The Beatles!, the album most closely associated with this new era, was essentially the American equivalent of the group’s British LP, With The Beatles.3

And finally, consider that the release date for With The Beatles was . . .

November 22, 1963.

It’s almost enough to make you want to accompany this whole story with the theme from The Twilight Zone.

Or at least “Revolution 9” — that frightening, disturbing collage of musique concrete on Side Four of The Beatles’ White Album, meant to capture in sound the chaos and turmoil of a year, 1968, that included, among myriad global instances of violence and upheaval, another assassination of another Kennedy.

Yeah, “Revolution 9” would be even more appropriate. It was released that year on . . .

November 22.

The teen idol trend in particular had been growing for years, hastened by the departure, for various reasons, of many of the seminal rock and roll acts of the 1950s: Elvis had entered the army in 1958 (and emerged in 1960 a different, less threatening figure); Jerry Lee Lewis was buffeted by scandal over his marriage to his 13-year-old cousin; Little Richard had gone into the ministry; Chuck Berry was arrested and imprisoned for violating the Mann Act; etc. The plane crash in February, 1959 that took the lives of Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and The Big Bopper put a tragic exclamation point on this exodus. While many fine records would be made over the next few years (and groups like The Four Seasons, The Beach Boys and The Isley Brothers would enjoy their first successes), the majority were the product of professional songwriting teams such as Leiber & Stoller, Goffin & King, Holland-Dozier-Holland, Bacharach & David, Mann & Weill, and Barry & Greenwich (most of them associated, figuratively if not literally, with The Brill Building). The writers sometimes acted as producers and musical svengalis for the singers who, other than the vital artists recording for black-oriented labels like Motown, Stax and Atlantic, were increasingly homogenized personalities groomed intentionally to be harmless commodities: we’re talking people like Frankie Avalon, Fabian, Pat Boone, Annette Funicello, Chubby Checker, and the Bobbys Vinton, Vee and Rydell. The few talented young artists who wrote their own material — Neil Sedaka, Paul Anka, etc — were marketed similarly and were essentially indistinguishable from the manufactured pop singers. And though terrific early soul and funk records existed, mainstream radio wasn’t about to play Otis Redding or James Brown. As if to ensure the mediocrity of the airwaves in the weeks after Kennedy’s assassination, even the Brill Building and Motown had precious few notable records out, The Four Seasons were absent, and the Beach Boys had only the maudlin In My Room and the conservative Be True To Your School. In short, the two-month post-assassination, pre-Beatles period was a true musical vacuum.

Introducing The Beatles, which was the American equivalent of their debut British LP Please Please Me, was actually put out by Vee Jay Records just before Capitol released Meet The Beatles, but it didn’t crack the Top 10 until the end of February. Beatlemania’s spectacular spread was initially focused almost completely on Meet The Beatles! and “I Want To Hold Your Hand.”

The two records shared much of the same track listing along with the iconic Robert Freeman group photo. The main differences were that the American LP included the hit single “I Want To Hold Your Hand” along with its British and American B sides, “This Boy” and “I Saw Her Standing There,” while the British LP had more songs, 14 as opposed to 12. (Capitol would take 5 tracks from With The Beatles and include them on The Beatles’ Second Album).

The connection is temporal—a coincidence of timing. That's not to say, however , that music, as the grand diversion and inspiration, was not more than welcome at such a time in America. But, surely, the fresh nature of the Beatles' creativity was irresistible, regardless of time or place.